(Click here for Part 1 and Part 2 of this series. This is the final installment of a 3-part blog series, excerpted from a work-in-progress by Rachel Brewer. Comments and feedback are welcome and may be directed to brewer@providencestl.org)

How Should We Approach History?

It is hardly possible to overestimate the effect of the physical environment upon a person’s life, especially in earlier ages when the influence of tunnels and canals, steam and electricity, biological and radar technology had not yet overcome and harnessed nature. Once natural boundaries and obstacles could not be so easily disregarded; trade routes, group migrations, and military campaigns alike had to follow certain lines. Perhaps one of the most powerful driving forces in settlement through history has been the need for water. Also, a person’s food and clothing and dwelling and industries and artistic creations were dictated to them largely by the materials available in their immediate neighborhood. Fear and appreciation of the forces in nature long influenced religion. Even today, if we travel, we find different ethnicities, languages, customs, governments, and religions in different lands. These differences are due, in part, to geography.

The question “When?” is no less important to the student of history than “Where?” To trace the progress of civilization and to understand historical relationships, it is necessary to know when things happened or existed. Every important event has its causes and results, and to learn them, we must know what preceded and followed the event. Human society in any place at any time consists of many particular things and persons, events and customs. These go together, and what unites them is their simultaneous occurrence. They are a bundle of sticks which must be tied together with a date. Moreover, the effect of an event upon society depends greatly upon when it happened, for circumstances might be favorable at one time and not at another. It is true that many social conditions which have existed for a long period began and disappeared so gradually that it is impossible to date them precisely, and one must be content with such approximate expressions as “the thirteenth century,” “the early Roman Empire,” and “the later Middle Ages.” Other events which undoubtedly did happen within some particular year we are also unable to date because of lack of reliable source material. But the object of the history student should be not so much to fix exact dates in your memory as to be able to list events in their proper sequence, to associate closely together simultaneous happenings, and to cultivate a sense of the lapse of time—to be able to realize, for instance, what five hundred years ago actually means.

The Historical Approach is Sympathetic—History is not a mere record of events, but instead tries to understand the life of the past. As we journey to the past, we must first, to the best of our ability, free ourselves from the burden of present prejudices and perspectives. We must forget for the time being whether we are liberal or conservative, man or woman, Protestant or Roman Catholic, Irish-American or African-American. To see the scenes of the past truly, we must borrow the eyes of the past. What people did then will mean little to us unless we comprehend their motives, their ideas, their emotions, and the circumstances under which they acted. One of the greatest benefits we can derive from the study of history is the entering into the life and thought of other people in other times and places. Thereby we broaden our own outlook upon the world as truly as if we had traveled to foreign countries or learned to think and to express ourselves in a language other than our own. We learn to approach differences of belief, tradition, experience, or preference with humility and generosity. When we broaden our experience with humanity’s astounding variety, we strengthen our defenses against a natural, human fear of the unknown. History alone makes it possible for us to travel both in time and space.

The Historical Approach is Also Critical—The student of history should, however, be critical as well as sympathetic. Truth is always our aim: a thorough understanding of the past as it really was. We must not believe everything that the people of the past tell us about themselves or others, but instead get to know them well enough to tell when they are trying to deceive us or themselves. We must be aware of their failings and prejudices as well as of their motives and obstacles. We must not allow ourselves to be swept off our feet by excessive enthusiasm for some person or ideal or institution of the past; we must seek to preserve a balanced and open-minded attitude. We ought to be wary of sensational and miraculous stories and dramatic endings; we should make allowance for the tendency of human nature to exaggerate and spin a good tale whenever there is the slightest opportunity.

The Error of Justification—Two equal but opposite pitfalls lie in the path of the historian: the temptation towards justification on the one hand and condemnation on the other. Our honest desire to understand the motives, ideas, and circumstances of the past may sometimes, if we are not careful, lead us too far. We might begin by explaining, but end up excusing the corruptions and evils of the past. In his famous 1895 address to Cambridge University, historian Lord Acton warned students against the impulse to judge the past by a different standard of morality than they would judge the present: “I exhort you never to debase the moral currency or to lower the standard of [righteousness], but to try others by the final maxim that governs your own lives, and to suffer no man and no cause to escape the undying penalty which history has the power to inflict on wrong.” He went on to explain that it had become common practice “to praise the spirit when you could not defend the deed. So that we have no common code; our moral notions are always fluid; and you must consider the times, the class from which men sprang, the surrounding influences, the masters in their schools, the preachers in their pulpits, the movement they obscurely obeyed, and so on, until responsibility is merged in numbers, and not a culprit is left for execution.”[ix]

Despite modern views on the issue, true morality does not shift with the times. The Good, the True, and the Beautiful are transcendent and eternal. Therefore, it is by a fixed moral standard that we must evaluate all of human history. The great statesman, political theorist, and philosopher Edmund Burke once wrote, “My principles enable me to form my judgment upon men and actions in history, just as they do in common life, and are not formed out of events and characters, either present or past. History is a preceptor of prudence, not of principles. The principles of true politics are those of morality enlarged; and I neither now do, nor ever will, admit of any other.”[x]

The Error of Condemnation—The 21st century historian is far more likely to encounter a pitfall of quite the opposite sort, however. Where historians have intentionally moved away from the justification of history, there has been an over-correction into the territory of broad condemnation. Today we are far more likely to view the ignorance and errors of the past with a kind of contempt and scorn, and to condemn—absolutely and without investigation or benefit of doubt—all people and perspectives that fall outside what is culturally acceptable in the present. C. S. Lewis coined the term “chronological snobbery” to describe “the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that account discredited.[xi] We are prone to view ourselves and our own society as far more advanced and, therefore, inherently superior to the people and societies of previous eras. One specific example Lewis presents of this chronological snobbery is the derogatory use of the term “medieval” to describe something as backward, ignorant, or obsolete.

A related fallacy is that of thinking historical people had the same perspectives and information we have today on which to base decisions and beliefs. When we read about historical people thinking or acting in ways contrary to modern science, medicine, or philosophy, we might be tempted to assume that the humans of the past were less intelligent than humans today. Instead, we should understand them as operating, through no deficiency of character or intellect, from a very different knowledge base and understanding of the world around them.

Conclusions—So, how should we approach history? The answer might be summed up in this way: With humility and gratitude; with caution and discernment; with clear moral principle; and with the same spirit of generosity we hope future historians will extend to us.

END NOTES

- [ix] Acton, Lord. 1895. “Inaugural Lecture on the Study of History.” Lectures on Modern History. ed. John Neville Figgis and Reginald Vere Laurence (London: Macmillan, 1906).

- [x] Burke, Edmund. Correspondence of Edmund Burke. Cambridge University Press, 1910.

- [xi] Lewis, C. S. Surprised by Joy. 1955. HarperOne Reissue edition, 2017.

- While most of the text featured here is my original work, the project from which this chapter originates is, essentially, a massive revision and expansion of the book History of Medieval Europe (1917) by respected historian Lynn Thorndike, which is now in the public domain.

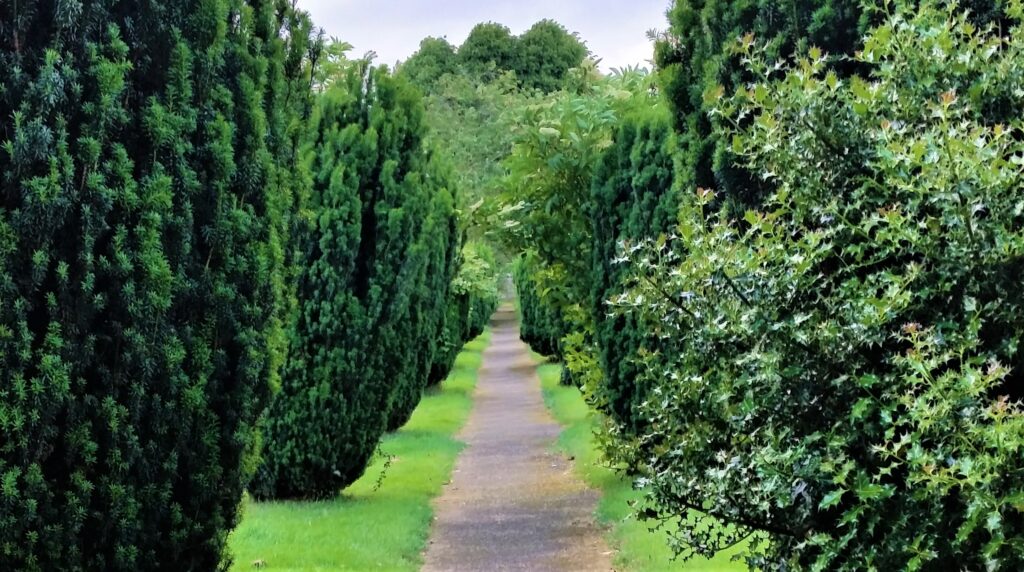

- Cover photo was taken by the author at St. Mary’s Church in Belford, England.

Ms. Rachel Brewer is enjoying her ninth year of teaching and her fifth year at Providence. She teaches upper school British and American Literature, Rhetoric, Senior thesis, and Medieval History. Rachel has her BA in History from Southern Illinois University and her MA in Medieval Archaeology from Cardiff University in Wales, U.K. She has enjoyed making her home in St. Louis and attends Trinity Church Kirkwood.