(Nota Bene—Click on the links scattered throughout this article to learn more about the history of books, the creation of medieval manuscripts, and the illumination process! Citations also linked.)

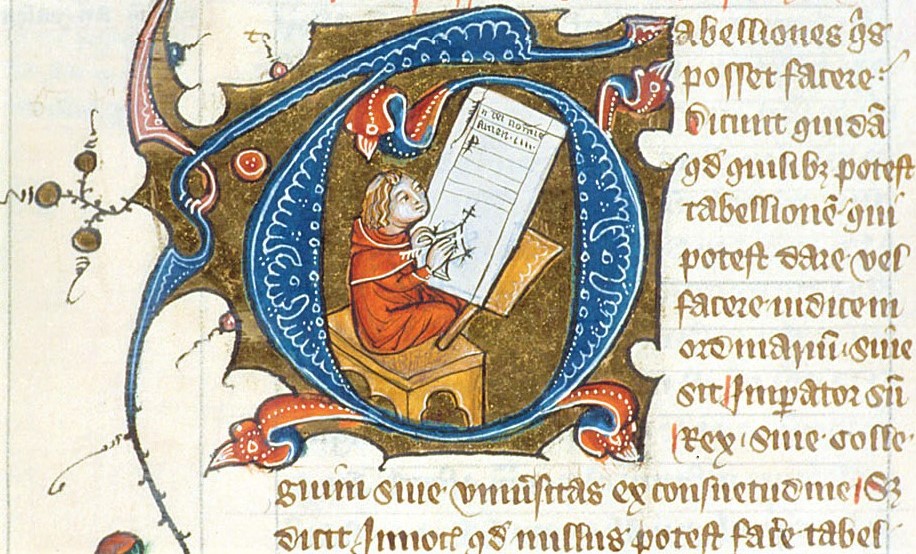

In a world inundated with mass-market books, junk mail, magazines, and paperwork, it can be difficult to imagine a time before printing technology. Before the 15th century, every word a person saw in their lifetime would have been painstakingly formed, letter-by-letter, by the careful hand of a monk or professional scribe. The books (i.e. manuscripts) in circulation were bound bundles of parchment (paper made from animal skins), each page of which was covered in meticulous text and often richly illustrated. The weeks and months—sometimes even years—of laborious copying alone would have made each manuscript valuable; but add the enormous effort and expense of preparing the parchment, creating the ink and color pigments, and applying gold leaf to make the illustrations shimmer in candlelight, and the product is nothing short of a treasure.

Relatively few people living in the Medieval period were fortunate enough to learn to read, and even fewer could own even a single book. The great 14th-century scholar Petrarch, sometimes called the “father of the Renaissance”, is credited with first referring to the time between the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the dawn of the Renaissance as a time of ignorance and error, an age of darkness. While it is understandable and forgivable—if a bit snobbish—that Petrarch saw his own time as the sole heir to the wisdom and enlightenment of the ancients, 600 years of textual analysis, historical scholarship, and archaeological investigation have gradually revealed why characterizing the medieval period as “the Dark Ages” is incorrect. But this is another topic for another post, so let us return to the manuscripts!

One of the most frequently copied and illustrated texts in the Middle Ages was the Bible. Indeed, the very act of copying the stories of scripture and the words of Christ was viewed as an act of worship and personal devotion. The orderliness of the script, as well as the vivid colors and burnished gold leaf of the illustrations, reflected the orderliness of creation, the vividness of biblical accounts, and the illuminating truth and wisdom of scripture. Being a monastic scribe was not easy or comfortable, however, as the work itself was long, tedious, and physically demanding. Additionally, conditions in the scriptorium (the work room of the scribes) could be fairly miserable: cold, damp, and dark.

Among the most famous examples of early Irish manuscripts is the magnificent Book of Kells, a 9th-century Celtic volume containing the four Gospels in Latin. What makes this book so extraordinary is its “lavish decoration, the extent and artistry of which is incomparable. Abstract decoration and images of plant, animal and human ornament punctuate the text with the aim of glorifying Jesus’ life and message, and keeping his attributes and symbols constantly in the eye of the reader.” Some of the pages are just full-page, full-color illustrations—such as folio27v, which depicts the symbols of the four evangelists.

Here at Providence, history classes follow a four-year cycle of Ancient, Medieval, Early Modern, and Modern History (in high school, the final two years are taught as AP-option European History and U.S. History). I’ve taught 10th grade Medieval History for the last couple of years and have loved introducing my students to this amazing period of roughly 500 – 1500 A.D. In our first unit, which covers Celtic Ireland and Britain, we discuss the founding of early-medieval monasteries, the role of the Celtic monks in preserving literature and education in post-Roman Britain, and the richly-illustrated books they produced entirely by hand. In addition to the Book of Kells, these monks gave us the equally magnificent Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Durrow. Some of the most beautiful and treasured manuscripts from the later middle ages would be thousands of copies of Books of Hours: prayer books for daily use whose exquisite paintings “were intended to foster reflection and devotion.” It is partly in response to these texts that I must respectfully disagree with Petrarch and talk about the medieval period as an age, not of darkness, but of illumination.

In class we spend time looking at and appreciating pictures of illuminated manuscripts, but I wanted my students to better understand the labor, time, devotion, imagination, and craftsmanship required of the medieval scribes. So, I outlined a special project, the creation of “The Book of Providence,” for which each sophomore history student would design and produce their own “illuminated” page.

For their page, students first choose a short passage of scripture with rich imagery. Then they plan the layout of text and illustration. Third, they line their page and write out the text, carefully mimicking the style of script common in the 7th/8th centuries. Finally, they decorate the empty spaces using illustrations inspired by the text.

In the two years we’ve worked on this project, I’ve seen students produce some amazing, beautiful, imaginative, and sincere artwork. Even those who struggle artistically or didn’t want to do the assignment at first have demonstrated pride in their work. When all the manuscript pages are complete, the students display their work where the wider community can enjoy the beauty and truth that students have transmitted through their own labor, time, and devotion.

Finally, these pieces of art will be gathered into The Book of Providence. And hopefully, over the coming years, there will be more pages by many young 21st-century scribes to add to it.

Miss Rachel Brewer is in her seventh year of teaching; she came to Providence in 2017. She teaches upper school British and American Literature, Rhetoric, Senior thesis, and Medieval History. Rachel has her B.A in History from Southern Illinois University and her M.A in Medieval Archaeology from Cardiff University in Wales, U.K. She has a long-term vision of discovering the perfect pedagogical formula (alchemy?) for turning all her students into history lovers.